We’re Here Now

We arrived at El Yunque! In this section, you will learn about its history, our relationship with the Sierra de Luquillo, and the forest’s ecological dynamics that we love so much.

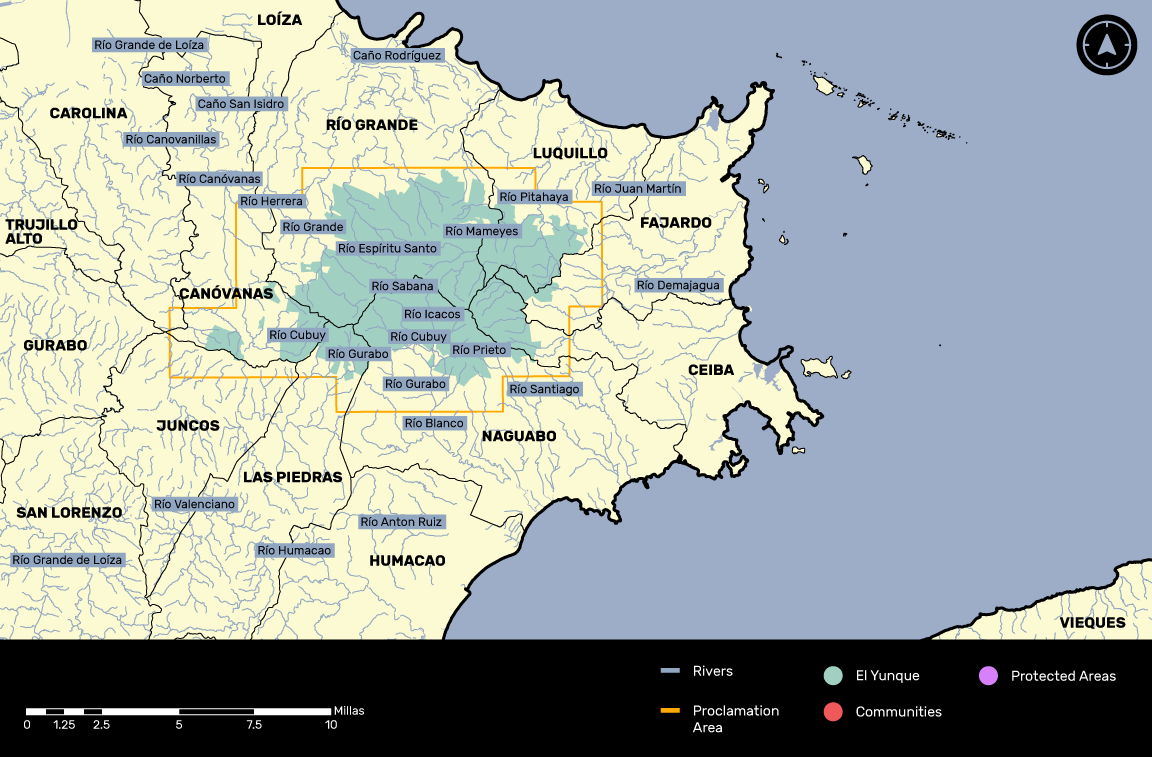

Let’s Find Ourselves on the Map

Extension

• The natural rainforest reserve covers 29,000 acres.

• Its size is 4 times that of the municipality of Florida.

• It neighbors the municipalities of Canóvanas, Ceiba, Fajardo, Juncos, Las Piedras, Luquillo, Naguabo, and Río Grande.

Water

• It rains approximately 152 inches annually.

• In the most elevated areas, it can rain up to 200 inches.

• It provides 20% of Puerto Rico’s drinking water.

• Approximately, 66 million gallons are extracted daily.

• This is where the rivers of Río Blanco, Río Espíritu Santo, Río Fajardo, Río Grande de Loíza, Río Mameyes, and Río Sabana are all born.

Flora, Fauna and Fungi

• 240 native trees live here.

• 26 endemic species live in El Yunque.

• It houses a variety animal species: 61 birds, 19 reptiles, 16 mammals, 15 amphibians, and 7 fishes.

• Approximately, 1,000 species of fungi and almost 200 types of lichens have been identified.

This forest a prime example of the housing of biodiversity. Here endemic, native and exotic species interact in a complex web of relationships that characterize this unique ecosystem. Scientists who study the forest thoroughly have denominated six types of forest, according to elevation and predominant species.

1. Riverside Forest

It’s found alongside rivers and streams in all elevations. This type of vegetation contributes to the good quality of the water and life present in the rivers.

2. Secondary Forest

In areas previously deforested by human activity, these forests are the result of reforestation and tend to combine native and introduced species. The forest at El Portal Trail is a good example of this classification.

3. Tabonuco Forest

In this forest, located between 150 and 700 meters in altitude, there are more than 80 species of trees, and many of them tend to reach 98 feet. Tabonuco (Dacryodes excelsa) and Motillo (Sloanea berteriana) predominate. The forest at El Angelito Trail is a good example of this classification.

4. Palo Colorado Forest

This type of forest exists in elevations between 600 and 800 meters, mostly in saturated soils. Up to 65 species of trees coexist, and some of them can reach heights of up to 50 feet. Palo colorado (Cyrilla racemiflora) predominates. Read more. Furthermore, it is very common to see many bromeliads and aerial roots. At this altitude, the fog from clouds that come from the Atlantic is predominant and covers the forest’s peaks.

5. Sierra Palm Forest

It tends to occupy steep slopes at over 450 meters in altitude, and the Sierra Palm Tree (Prestoea montana) predominates, which tends to survive hurricanes quite well and produces fruit that serves as food for the Iguaca, the Puerto Rican Parrot.

6. Tabebuia and Eugenia Forest

Also known as Dwarf Forest or Cloud Forest. This forest dwells in the peaks and the highest areas of El Yunque, at more than 900 m above sea level. Read more. It is inhabited by more than 20 endemic species, and the Roble de Sierra (Tabebuia rígida), the Guayabota (Eugenia borinquensis), and the Giant Fern (Cyathea bryophila) predominate. Although few species adapt to these conditions, they are of vital importance, because they protect the peaks from erosion.

“…El Yunque is a monument of this nation, in which the texts of our time, history, and memory are inscribed. Only through contact, maintaining that physical tie with the environment, is it possible to perpetuate the memory, the language, the stories, and the totem.”

(Pizzini et al. 203)

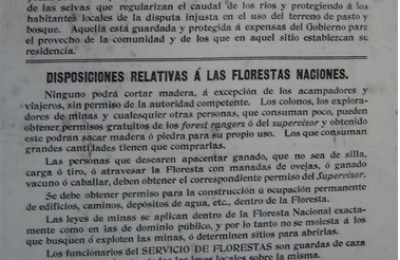

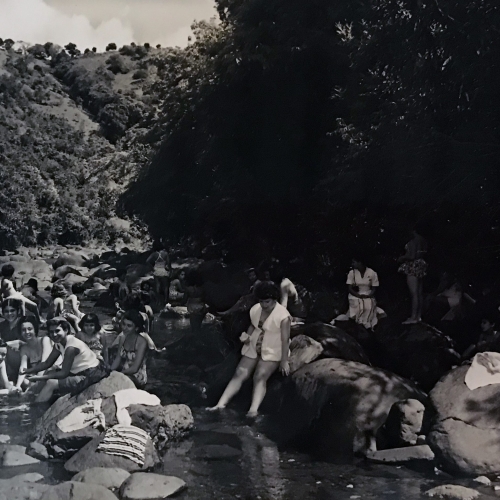

The Memory of the Forest:

El Yunque and Its History

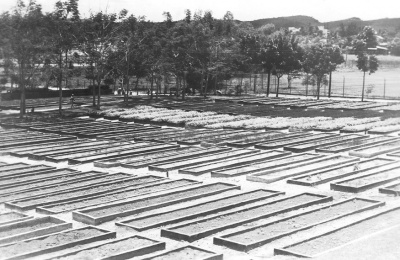

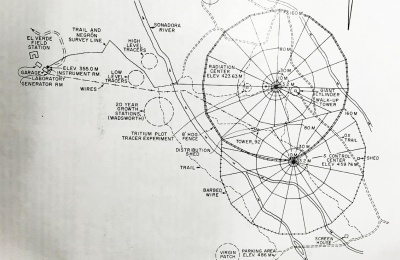

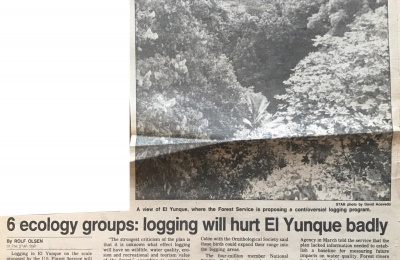

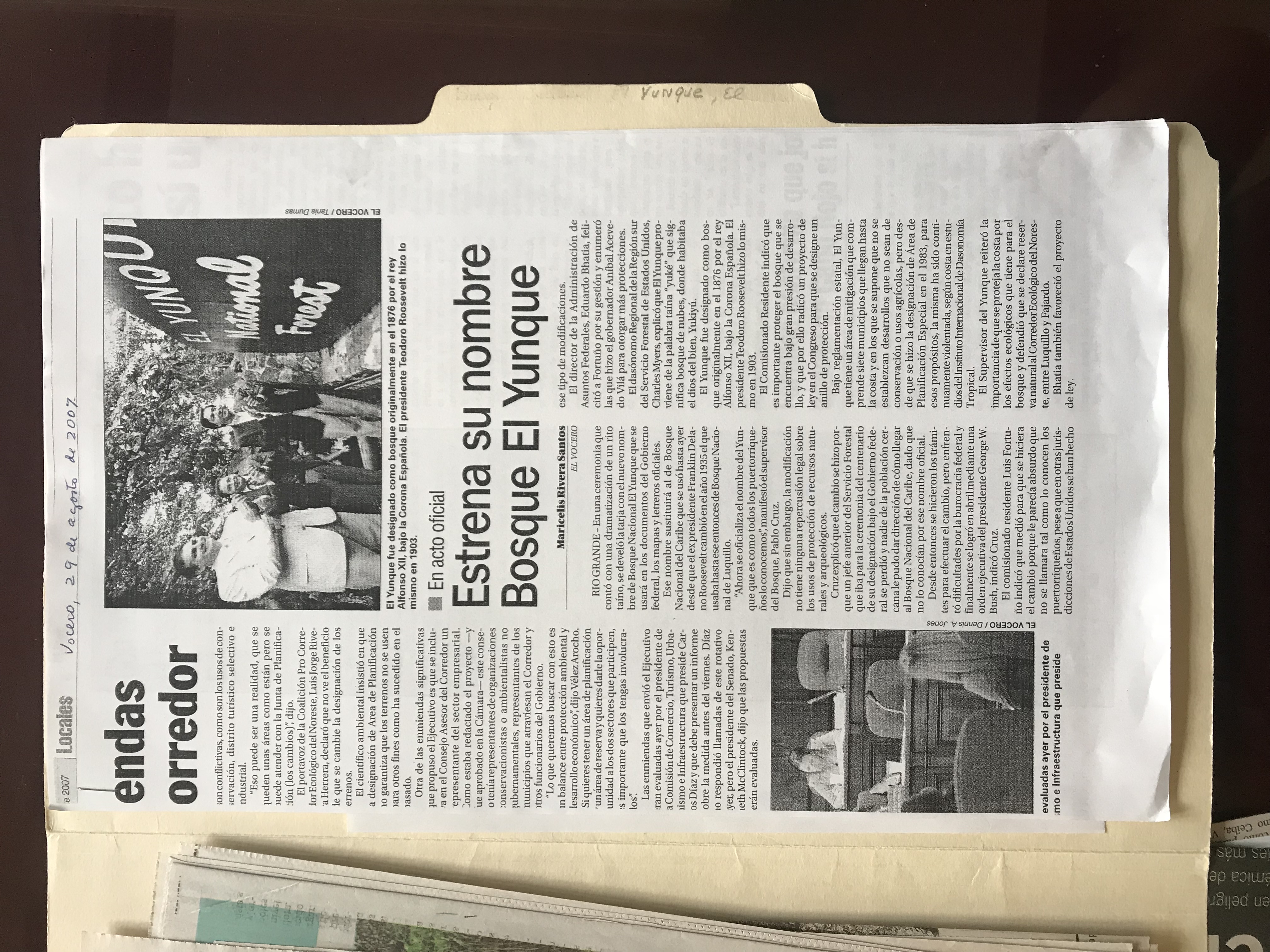

We’re also part of El Yunque. There is evidence of carboneras (coal cellars), agricultural practices, trails, recreational areas, and a variety of structures that speak as we walk through this forest. Our shared chronicle lives in petroglyphs, the historical documents, and our collective memory. Coming up, an album to remember.

Photo: Archivo General de Puerto Rico

The Forest Community:

Cooperation and Mutualism in El Yunque

In a neighborhood, the participation of every one of the neighbors and family members contributes to the wellbeing of the entire community. Something similar occurs here in the forest, since the function of every one of the organisms contributes to the balance of the entire ecosystem. Let’s look at some examples of cooperation and mutualism in El Yunque. These interactions among species who support one another contribute many benefits and bring prosperity to the forest.

Yagrumo hembra

Cecropia schreberiana

Are you familiar with it? When El Yunque loses many of its trees due to strong hurricanes, for example, this species takes advantage of the sunlight, grows very quickly, and generates a temporary canopy.

So, other species can germinate and grow beneath its shadow. Hence, it is considered key and pioneering in the rehabilitation of ecosystems after a natural disturbance or large tree-cutting. Surely, yagrumo hembra is growing today, along with other species, and supporting the recovery of our rainforests.

For more information about Yagrumo Hembra, you can go here.

Photo: Flora Virtual Estación El Verde

Photo: Flora Virtual Estación El Verde

Photo: Flora Virtual Estación El Verde

Photo: Flora Virtual Estación El Verde

The Ausubo and the Red Fig-eating Bat

Manilkara bidentata y Stenoderma rufum

How does a bat relate to a tree? It’s simple; the tree bears fruit that the bat eats; the bat digests the fruit, and when it defecates in the forest, it spreads the ausubo seed.

It’s a super great exchange! So, if we find Ausubo trees along the way, it is very likely that a bat planted them.

For more information on the Ausubo, you can go here.

Photo: Erick Calderón

Photo: Flora Virtual Estación El Verde

Photo: Erick Calderón

Photo: Erick Calderón

Tabonuco

Dacryodes excelsa

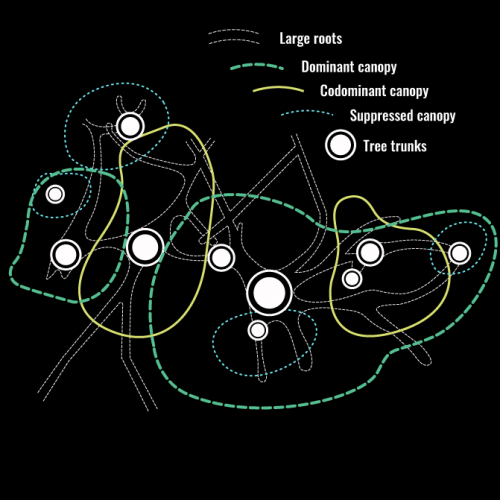

The Tabonuco knows that there is strength in unity. Its communities connect through their roots forming an exchange network of information, nutrients, and organic matter that gives them more opportunities for survival. This tree is historically beloved. Its wood is formidable for construction, and its aromatic resin has been used as an insect repellent and as raw material for the confection of candles and medicine.

For more information on the tabonuco tree, you can go here.

The forest community is an example on how we can organize our daily social dynamics. From the small nuclei of our families, communities and schools, we have the opportunity to interact with one another in balance, supporting one another as the forest does.